Reducing water needs

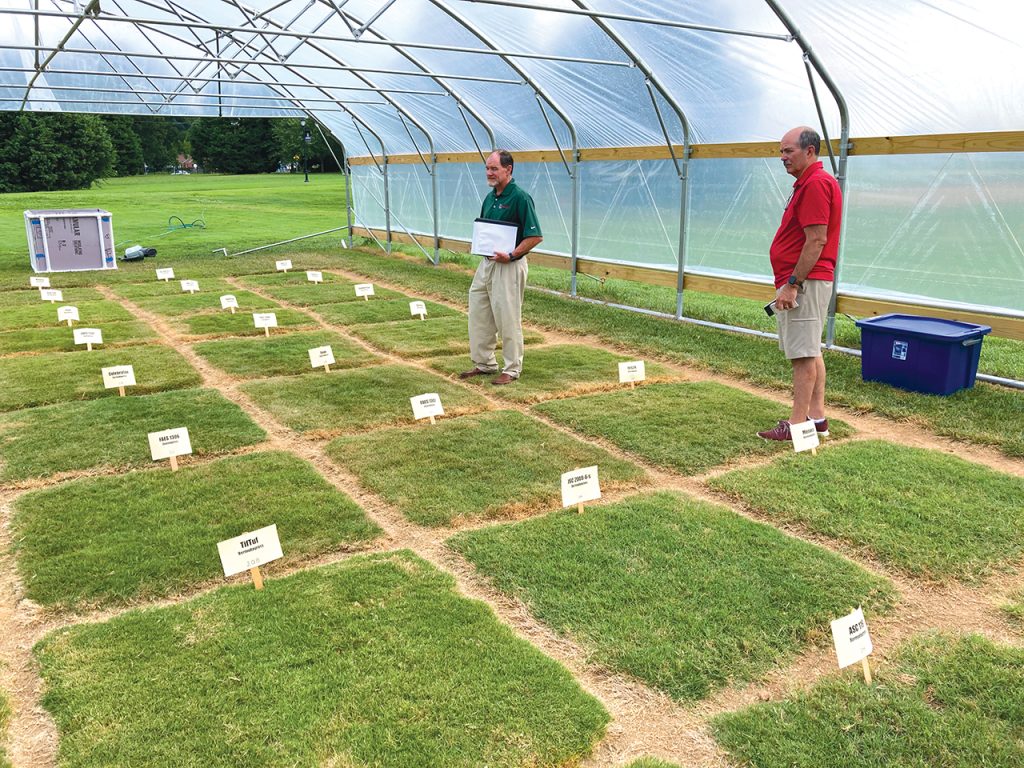

Turfgrass trials at UGA Griffin campus. Clint Waltz, University of Georgia (left) and Kevin Morris, Executive Director of the National Turfgrass Evaluation Program (NTEP).

Turfgrass research yields new varieties

by Mary Kay Woodworth, Executive Director, Georgia Urban Ag Council

“It’s not easy being green,” goes the saying. As far back as 1975, the legendary country and blues singer Ray Charles of Georgia, USA, with the 1960’s hit “Georgia On My Mind” recorded the song “Bein’ Green.” Charles sang: “It’s not easy being green. It seems you blend in with so many other ordinary things, and people tend to pass you over ...”

It’s not easy, either, for turfgrass growers and associated businesses, for whom “green” is crucial to the industries they have built and the jobs they have created for so many. Their customers and the communities they serve strive to be green.

For well over a decade, in Georgia and in communities across the globe, outdoor water use – especially on turfgrass - has often been vilified and labeled as wasted water. The numerous benefits of turfgrass have conveniently been ignored by the anti-turfgrass community, whose viewpoints are narrowly focused.

Turfgrasses occupy over thirty million acres in the U.S. It’s tempting to assume that eliminating our outdoor grass carpeting could solve the water demand problem. But it’s not so simple. Turfgrass provides substantial environmental and economic benefits in our landscape. It mitigates heat around our homes, stabilizes soil against erosion, provides safe play space, and reduces noise, glare, and pollution. Eliminating turf would create a whole new set of environmental challenges.

The implementation of sustainable landscapes should be a goal in all regions of the country; however, severe droughts and limited water in the southern and western U.S. are dictating changes to the use and placement of plant material and irrigation in landscapes. Therefore, there is a critical need for turfgrasses that can provide functional surfaces tolerant to drought, reduced irrigation, and irrigation with reclaimed (saline) water. Failure to address these challenges will result in losses of areas planted in turfgrasses, along with their economic, environmental, and social benefits.

Working toward a solution

A network of turfgrass researchers from six major universities was formed in 2010 to address the above problems. The researchers from the University of Georgia, NC State, Oklahoma State, Texas A & M, University of California-Riverside, University of Florida, and USDA are solving this dilemma by developing turfgrasses that are attractive and healthy with minimal water.

In 2020, The National Institute of Food and Agriculture approved a specialty crops grant to continue the multi-university group’s work producing drought-tolerant warm-season turfgrasses. The team (32 scientists strong) has collaborated for nine years with a rotating leadership structure. Currently, NC State’s Susana Milla-Lewis is at the helm in their new phase of study.

“Our 2010 and 2015 projects were crucial in the development of drought-tolerant turfgrass cultivars. The levels of improvement of these grasses are promising and validate the need to promote adoption, continue cultivar research, and develop tools that facilitate the breeding process.” ~ Susana Milla-Lewis, NC State

The team of turf researchers’ work has focused on selecting and testing drought-tolerant cultivars of four of the most economically important warm-season turfgrass species in the southern US. By exchanging plant materials and data among university breeders, turf varieties are tested under many climatic conditions, and the results accumulate quickly.

“The collaboration among breeders across such different environments is priceless,” Milla-Lewis said. “It helps us select better lines with more performance stability because they have been tested against a wide range of weather conditions like drought and cold as well as an array of pests and diseases.”

The team has already released six new drought-tolerant varieties from previous project phases including two bermudagrasses (‘TifTuf’ and ‘Tahoma 31’), two St. Augustine grasses (‘TamStar’ and ‘CitraBlue’), and two forthcoming zoysiagrass varieties.

‘TifTuf,’ a University of Georgia release, alone has achieved massive success. The team’s research demonstrated a 40% water savings over the leading bermudagrass, without loss of turf quality. This convincing research data has led to the rapid acceptance of TifTuf within the sod industry – representing a six-fold return in gross earnings compared to the grant investment.

Gearing up with technology

With tangible success already, what will the next research phase include? More trials with new avenues to share and test them.

Plant breeding is a long-range game, 10-15 years in most cases. The group has already evaluated over 2,500 potential varieties in their nine years together. Now the team is intent on warping this speed with innovative technology.

The group’s next phase of research will integrate tech specialists using drones and remote sensing devices to provide real-time feedback on plant stress – a plant breeder’s dream. But how does a robot sense plant stress?

Drones equipped with specialized sensors will be programmed to fly missions over the test plots to detect changes in turf color, ideally even before visible to the human eye. By measuring color change over time resulting from turf stress, researchers can rank the highest performers and concentrate on those showing the greatest genetic potential.

Technology also brings objectivity to plant breeding. Instead of researchers assigning a visual grade of 1-9 on turfgrass color, the drone sensors capture a binary “stress/no stress” assessment. It’s black or white – or brown or green in this case. Removing human bias will result in standardized scoring – important when measurements are taken across hundreds of plots at each of the six universities. Because who’s to say someone’s turf score of “6” in Raleigh is the same “6” as someone’s in Texas?

Using autonomous data collection, breeders can measure more traits, evaluate more trials – and even more varieties at a time. Increasing the volume of data generated in a short timeframe speeds the plant breeding process by weeding out low-performing options. Researchers call it ‘high throughput phenotyping” and it promises to deliver fast feedback for a streamlined selection funnel.

Greater testing volume into the research pipeline means better outcomes with the most resilient samples.

Outreach and education

Despite the team’s field research success, Milla-Lewis’s group recognized that improved varieties can’t deliver their inherent benefits if end users don’t adapt their lawn care. For that reason, the project’s phase III incorporates a significant extension and consumer outreach plan spearheaded by Jason Peake at the University of Georgia.

As new cultivars are released into the market, a shift in outreach efforts is needed to reach a broader sector of society with an interest in application rather than basic knowledge behind drought tolerant turfgrasses. Among urban consumers, water purveyors, and other decision makers, the objective is to increase awareness of new cultivars and research-based management strategies that reduce water inputs.

The nationwide campaign will include broadcast media, a consumer decision tool website and printed marketing pieces all aimed at educating consumers on why they should choose a drought-tolerant grass and, importantly, how to effectively manage it to reap all the benefits. After all, a new lawn doesn’t come with a care tag.

This new wave of consumer outreach will complement traditional extension activities such as field days and demonstration turf plots at public locations like municipal complexes, campuses, parks, and athletic fields. These opportunities will reach industry professionals like landscapers, contractors, and sod-producers who are often the decision-makers in turfgrass variety selection.

NC State turfgrass extension specialist Grady Miller says it’s not enough just to put new varieties out. “Like the old saying goes ‘Those near the cutting edge may get cut’.” Our efforts can convince the industry to adopt and produce, but the consumer needs to be able to properly manage the turfgrasses if we want these new varieties to be successful.”

“We’ve learned in our investigations that the average consumer is concerned about their grass’s environmental tolerance – to shade, drought, and winter-kill. They are looking for low-maintenance landscapes,” Milla-Lewis noted.

Convincing homeowners to adopt these drought-tolerant grasses would deliver on both accounts. “We have a young consumer audience with vastly different landscape needs. For some, lawn maintenance is at best a hobby, and at worst a nuisance. They are looking for lawns requiring fewer inputs, even if it is more expensive,” concluded Miller.

As additional drought-tolerant turfgrasses are developed and brought to market, local governments should encourage and incentivize homeowners and property owners to utilize these water saving varieties. An example of this is the recent measure taken by the Metro North Georgia Water Planning District (Metro Water District).

Oversight for water conservation and planning for the communities in the metro-Atlanta area is the responsibility of the Metro Water District. After months of engagement by landscape industry advocates, along with supporting testimony from Dr. Brian Schwartz (a member of the University of Georgia’s turfgrass research team), the planning district’s board voted to support and promote education to the public that “encourages the installation of drought tolerant sod such as TifTuf.”

This includes updating the district’s printed and digital education materials on landscape and irrigation resources to include drought-tolerant turfgrasses.

Impacting the future

TifTuf, Tahoma 31, and the tireless efforts of Dr. Schwartz and others like him, along with many turf and landscape leaders, will continue to make being green even more positively impactful in the future. Proper soil preparation and utilization of these new varieties, in conjunction with professional irrigation design incorporating new, efficient technologies will yield reduction in water use. Adding WaterSense labeled irrigation controllers can contribute to significantly reduce overwatering by applying water only when plants need it – another valuable tool to efficient outdoor water use.

No, “it’s not easy being green,” but with additional research and new water-saving turf cultivars available to consumers, being green is getting easier each day. Let’s all do our part to educate and encourage consumers to adopt these new opportunities.

Contributing to this article: Tolar Capitol Partners, NCSU Turfgrass Science and UGA Turfgrass Innovations